Investment Insights Blog: Why Not Just Invest 100% in Stocks?

By Frank Holsteen

Managing Director, Investment Management

I came across some online debate recently that centered on a question which I’m sure many investors have asked themselves: If stocks tend to have the highest expected returns, why shouldn’t I invest my entire portfolio in them?

This version of the debate was sparked by a recent study, "Beyond the Status Quo: A Critical Assessment of Lifecycle Investment Advice," which concludes that retirement savers would be better off owning 100% equities over their lifetime.

The researchers examined a hypothetical average U.S. couple who save and invest as they work and then withdraw from their savings during retirement. Using historical data, they measure how much that couple would have earned if they invested solely in stocks vs. several other options, including a target-date fund and a money market-style fund. The all-stocks option—specifically a mix of 50% U.S. stocks and 50% international stocks—created more wealth at retirement than all others.

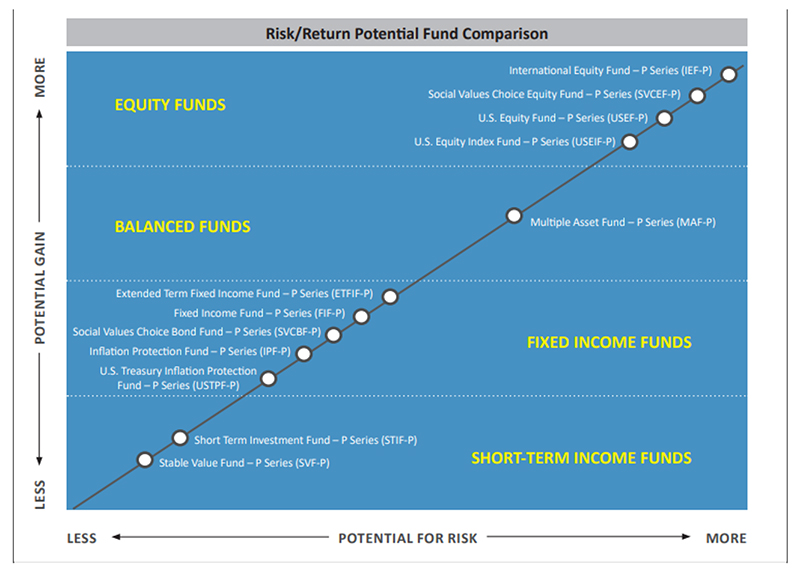

In many ways, these results are not very surprising. Stocks are generally considered to have the highest expected long-term returns, so if you’re an investor with a lot of time, like a couple saving for retirement, you’d expect those investments would do quite well. Here at Wespath, we anticipate that our equity funds offer the highest potential gain:

(Source: Wespath, Investment Funds Description – P Series, intended to show relative levels of risk/gain potential among the funds, not absolute levels of risk/gain potential for any individual fund.)

Of course, there's a word that appears in our chart that's missing from the study’s analysis: risk. The researchers are focused simply on total returns, not risk-adjusted returns.

But why does that matter? Why should a retirement saver, or a non-profit that invests charitable assets, worry about risk-adjusted returns? There are good reasons to, but before we answer those questions fully, let’s talk more about what "risk" really means.

What is Risk?

There are many different types of risks in the investing world. You may have heard of concepts like “geopolitical risk”—which is the risk that government policies and political events can impact the value of investments—or “inflation risk,” which describes the risk that investments lose value over time because of inflation. These are just two examples among a very long list!

In some ways, risk is simply a reminder of a powerful life lesson: just because things turned out one way doesn’t mean there wasn’t a reasonable probability it could have turned out differently. The COVID pandemic comes to mind here—things were bad when the pandemic hit, but they could have turned out a lot worse than they did, had it not been, in part, for safety precautions, vaccine development and economic stimulus measures.

As investors, what we’re really talking about here is the ability to measure risk. One very common risk measurement is volatility. This is a measurement of how much an investment’s value fluctuates over time. It is not the only way to measure risk, and it is not the be-all, end-all method to understand one’s exposure to risk, but it can be a helpful gauge. High volatility indicates a greater chance of significant price swings, both up and down. Publicly traded stocks are typically more volatile than “safer” investments like bonds issued by the U.S. government.

But when we think about measuring risk in terms of volatility—the scale of the up and down swings we’re likely to experience with an investment—we start to understand why one might not want to commit their entire portfolio to a single investment type.

Why Risk Matters

My main reason for recommending that investors consider risk-adjusted returns is really a psychological one. Of course, if things play out like they did for the hypothetical couple analyzed in the study, a retirement saver could just put their whole account in stocks, never think about it until the day they retire and then start to draw down their savings. But we know that’s not the experience most people have.

In practice, it’s very hard not to react to short-term events. Human beings are psychological creatures. If we’re checking our retirement statements every quarter, we might have trouble resisting an emotional decision or trying to time the market, especially when we hit those rougher periods.

We also all deal with unexpected events. A retirement saver may have an emergency medical cost that forces them to withdraw more of their savings earlier than they anticipated to pay for a treatment. The same goes with non-profit organizations such as a church—perhaps a severe storm damaged a church building and the congregation needed to fund roof repairs. These things can and will happen!

These are the situations where volatility really matters. If you have investments that fluctuate dramatically in value and you must make a significant withdrawal when they happen to be down, you may have to sell those assets earlier and for a lower return than you planned for. Your ability to “wait it out” over the long-term has changed. Investing exclusively in high-volatility assets like stocks increases the likelihood that you’ll find yourself in that type of situation.

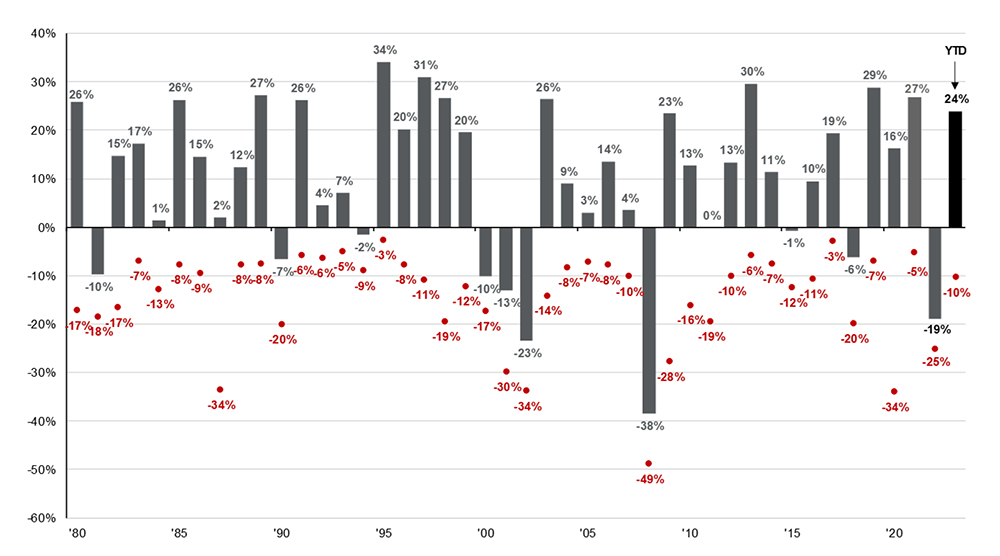

Take this next chart, for example. It shows both the calendar year returns and the biggest intra-year drawdown of the S&P 500 over the past four decades. We see that, even though returns were positive in most years, U.S. stocks average an intra-year decline of about 14%:

(Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management, “Guide to the Markets,” as of December 21, 2023)

Final Thoughts

With all this said, I don't disagree entirely with the authors of the study. To me, a reasonable conclusion from this analysis is less "I should only invest in stocks" and more "I might have more room for risk in my investments." I have certainly observed that many long-term investors could benefit from having a slightly greater appetite for risk over that long-term horizon.

Still, we must keep in mind: all investors are different, and there is no magic formula for balancing risk and reward that works for everyone all the time. The basic principles of diversification, managing one's emotions and preparing for unexpected events hold up, but our individual approaches to finding that balance will likely be unique.