Moody’s Downgraded the U.S. Credit Rating—Should We Be Worried?

By: Connie Christian, CFA

Manager, Fixed Income

The U.S. budget deficit took center stage earlier this month when Moody’s, one of the “Big Three” credit rating agencies, downgraded the U.S. government’s credit rating from the top-tier Aaa to Aa1. Moody’s was the last of the three major Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations (NRSROs)—alongside S&P and Fitch—to make this move.

In the days following the downgrade last week, U.S. Treasury yields spiked, with longer maturities exceeding levels reached during the early-April tariff volatility. This also coincided with federal budget negotiations, underscoring that U.S. government spending is very much in focus for investors right now.

A Little History

Moody’s was the first of the Big Three to assign a triple-A rating to the U.S., doing so back in 1918. In 2011, S&P downgraded the U.S. to AA+ for the first time, citing political gridlock and rising debt. Fitch followed in 2023, pointing to repeated debt ceiling fights and a lack of fiscal governance. Now Moody’s has followed, and the message is clear: the U.S. has a debt problem, and there is no clear plan to fix it.

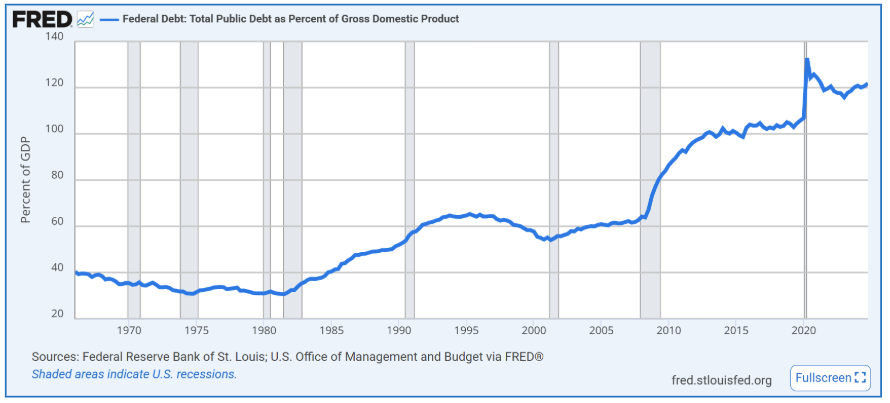

Since the S&P downgrade in 2011, federal government debt as a percent of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has risen from roughly 95% to more than 120%.

Total Federal Debt as a Percent of Gross Domestic Product

(Source: fred.stlouis.org)

The government’s increasing debt is important for several reasons. First, as the country’s debt burden increases, so too do interest costs, policy inflexibility in times of emergency, and concerns about the long-term financial health of the country. These potential consequences could have both domestic and global impacts, including higher tax burdens and market-related impacts such as higher interest rates and a weaker dollar.

AA is still a good rating, right?

Both AAA and AA ratings are considered high quality and low risk, with the higher rating indicating “extremely strong” creditworthiness and the lower “very strong.” This distinction is relatively minor, but it could impact how investors price in risk (remember: investors typically demand higher rates of return to compensate for more risk). For context, as of this writing, the U.S. Composite AAA yield curve shows a 10-year yield that is 0.10% less than its AA counterpart.

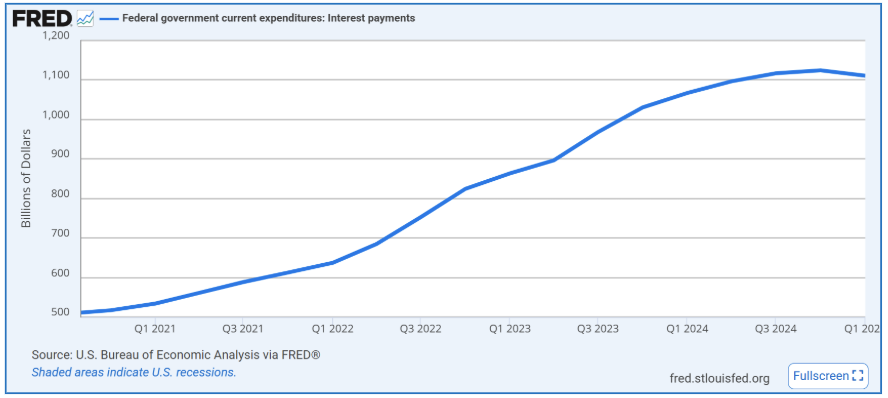

With that in mind, yes, credit ratings do influence Treasury yields, which determine how much the government pays in interest to bondholders. If investors start to see more risk, yields could rise. That would mean higher borrowing costs and bigger interest payments. For the U.S., a country that is already running large deficits, the compounding effect of higher interest payments could exacerbate fiscal stress and an already strained budget.

Federal Government Interest Payments

(Source: fred.stlouis.org)

Will the downgrade impact global trust in U.S. Treasury bonds?

In the immediate term, it’s unlikely. Despite the downgrade, U.S. assets will likely remain as some of the safest in the world. After all, the U.S. dollar and the U.S. Treasury market are deep, liquid and hard to replace. When S&P and Fitch downgraded the U.S., there was no mass exodus from U.S. bonds—and we’re not likely to see one now either.

With that said, discussions about the U.S. dollar’s eroding status as a global reserve currency are constantly in the news these days. Should the Moody’s downgrade add more fuel to this fire, we could see even greater concern about the U.S.’ leadership role in global financial markets.

A global comparison: The case of Japan

Japan offers an interesting case study. It has faced multiple downgrades over the past two decades due to its massive debt load—now over 260% of its GDP, the highest among advanced economies. Despite this, Japan has avoided a debt crisis.

Still, Japan's downgrades were accompanied by years of sluggish growth and low investor confidence. While the U.S. differs in many ways—particularly due to the dollar’s global role—Japan’s experience shows that while downgrades don’t always trigger a crisis, they can signal long-term economic challenges that can erode growth and fiscal flexibility.

So… does it matter?

Yes—but it’s important to maintain perspective. The Moody’s downgrade adds pressure and highlights growing concerns about America’s long-term fiscal health. But the U.S. still holds major advantages: a deep bond market, global economic influence and (for the time being) the world’s reserve currency.

In short: the downgrade won’t change everything overnight, but it’s a warning worth paying attention to.