A Pause in U.S. Exceptionalism: Shifting Dynamics in Global Markets

By Joe Halwax, CAIA, CIMA

Senior Managing Director, Institutional Investment Services

By Raj Khan, CFA

Director, Investment Research

The prolonged dominance of the United States in global equity markets appears to have hit a pause. From the beginning of the year through the end of April, the S&P 500 Index of U.S. stocks underperformed the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. Index by more than 16%. This marks a notable break from the long-standing trend of U.S. outperformance since the Great Financial Crisis in 2008. This development raises questions about whether the era of U.S. exceptionalism is undergoing a temporary pause or a more fundamental shift.

The Foundations of U.S. Exceptionalism

The U.S. exceptionalism has been rooted in several key characteristics: a massive, unified market with a single currency and language, relatively wealthy consumers, and a business-friendly regulatory environment. Wall Street has provided unparalleled access to debt and equity financing, while an entrepreneurial culture has attracted global talent, leading to world-leading companies. Silicon Valley’s venture capital ecosystem has further boosted technological innovation.

However, U.S. dominance has also been bolstered by weaknesses elsewhere. Europe’s population growth is stagnating, and the E.U. generally offers a stricter regulatory environment. China’s centralization of power and overinvestment in its housing market have constrained its economic growth. Brexit diminished the U.K.’s global relevance, while Australia and Canada focused on housing market growth at the expense of broader economic priorities.

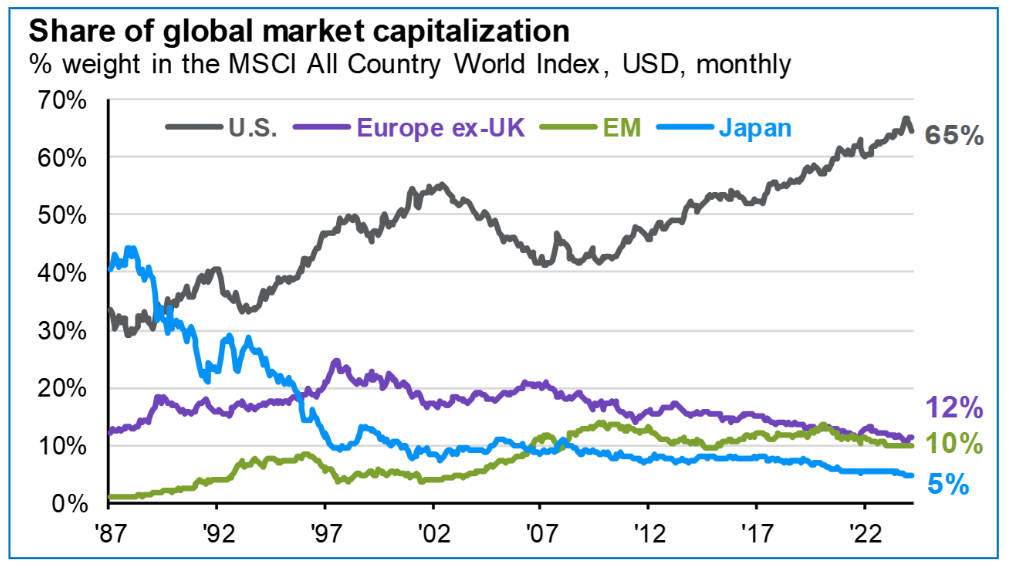

Against this backdrop, global capital naturally gravitated toward the United States, driving U.S. equities to represent approximately 65% of global market capitalization in 2025 (MSCI All Country World Index). This is up from 45% in 2009:

U.S Share of Global Stock Markets Near Multi-Decade Highs

(Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management, as of April 29, 2025)

What’s Changed Recently?

Recent developments suggest that U.S. exceptionalism may be faltering under domestic policy challenges. The Trump administration’s trade policies, including tariffs, have introduced higher input costs for businesses and invited retaliatory measures from trading partners. While these tariffs alone may not cause catastrophic economic disruption, they create an environment of uncertainty that discourages long-term investment and weighs on consumer confidence.

And this administration’s policy unpredictability extends beyond tariffs and trade. Frequent shifts in rules and erratic commentary—ranging from annexation proposals to undermining NATO alliances—have further eroded investor confidence. This climate makes it difficult for businesses to plan for the future, potentially stalling economic growth and innovation.

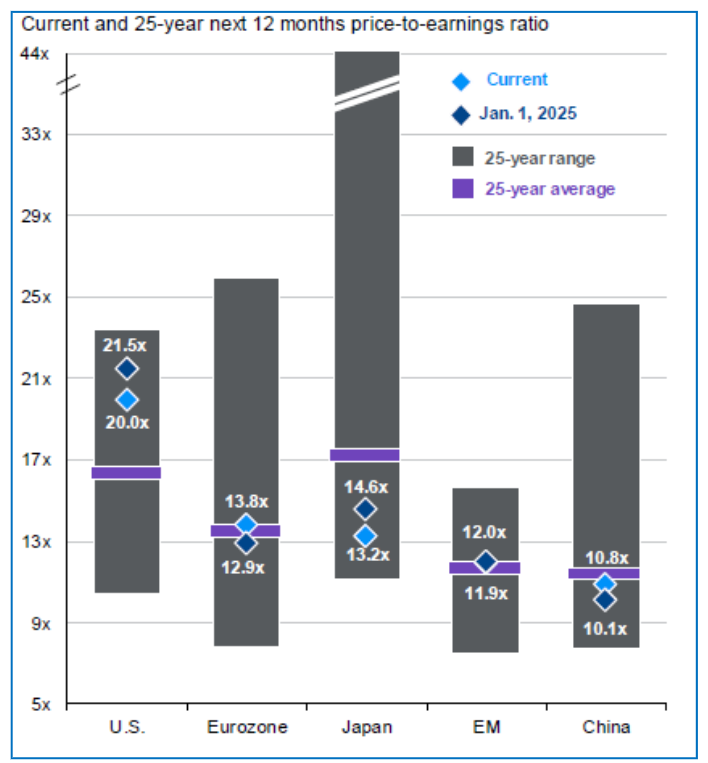

Moreover, the U.S. market faces relatively high valuations and interest rate uncertainty. The S&P 500’s forward price-to-earnings ratio is more than 19X, comfortably above its historical average range of 16X – 17X. Meanwhile, inflation remains above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target, and the outlook for interest rate cuts from the central bank is still unclear.

While uncertainty looms over the U.S., other regions are showing signs of recovery. China has stabilized its housing market and invested heavily in high-end manufacturing sectors such as electric vehicles, semiconductors and robotics. It is also emerging as a competitive force in artificial intelligence (AI); we note that the shift out of the U.S.’ Magnificent 7 and into international stocks accelerated sharply after the late January news of Chinese AI model DeepSeek. Japan’s corporate governance reforms are yielding positive results, while Europe is exploring more flexible fiscal policies under Germany’s new coalition government.

Although these changes are incremental rather than transformative, they have narrowed the valuation gap between U.S. equities and global markets. For investors seeking growth opportunities outside the U.S., these developments are promising, especially since current valuations still indicate steep discounts in contrast to U.S. companies and historical averages:

Global Valuations

(Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management, as of April 25, 2025)

The Role of the Technology Sector

The technology sector has been a cornerstone of U.S. exceptionalism, with mega-cap companies like Apple, Microsoft and Amazon driving much of the market’s gains. However, this dominance faces challenges. The recent surge in AI investments—spurred by advancements like ChatGPT—has led to significant capital expenditures. Rising interest rates and growing competition from international players like China’s DeepSeek model further complicate the outlook. Valuations in the tech sector remain high, making it vulnerable to downward revisions in earnings growth expectations. While these companies have historically delivered strong results, sustaining their momentum will require navigating rising costs and competitive pressures.

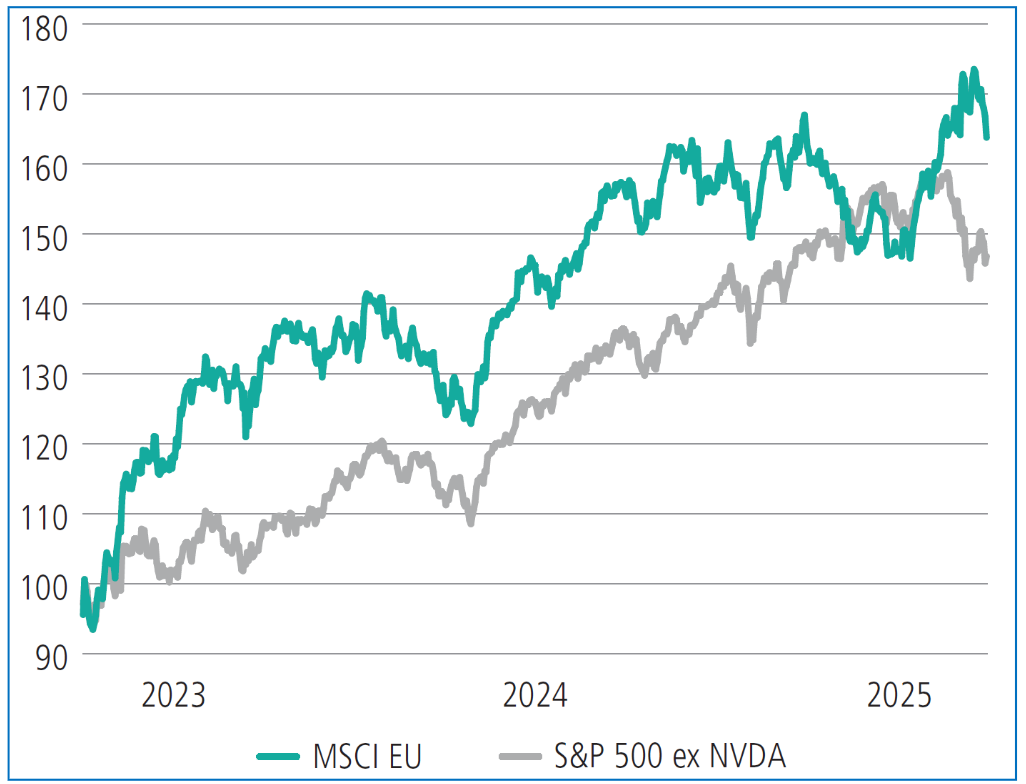

Also, while the industry has coined the term Magnificent 7, one stock has emerged as much more magnificent: Nvidia, the maker of high-powered chips used by AI large language models. The positive impact of Nvidia on U.S. returns is so large that, once removed, the MSCI Europe stock index has actually outperformed the S&P 500 in recent years:

European Stocks Outpacing S&P 500 ex-Nvidia

(Source: Neuberger Berman, as of March 31, 2025)

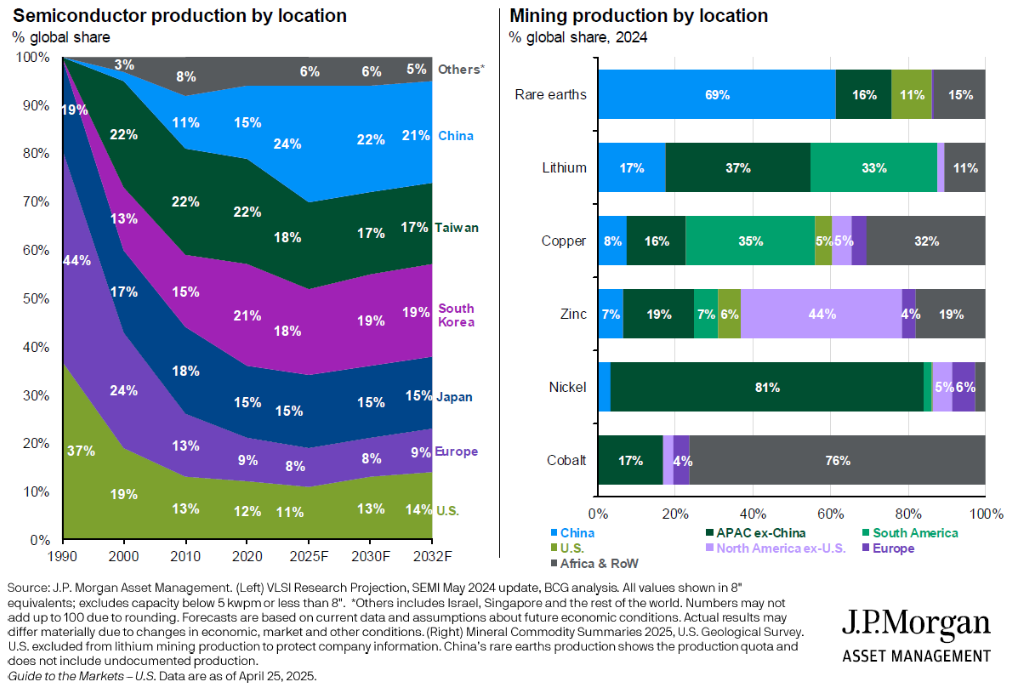

In addition to equity concentration in the technology sector, two other factors merit close attention: semiconductor manufacturing and mining production. As global demand for advanced chips and battery technologies accelerates, the geographic distribution of IT production becomes increasingly consequential. The U.S. share of global semiconductor manufacturing has declined to below 12%, while countries like China, South Korea and Taiwan have rapidly expanded capacity.

Although the CHIPS Act aims to revitalize domestic production, its forecasted impact is expected to be modest in the near term. The outlook is even more concerning in mining and mineral production, particularly for materials critical to electrification and the energy transition. The United States accounts for just 11% of global rare earth production, compared to China’s dominant 69% share. Similarly, lithium and nickel—essential components in electric vehicle batteries—are primarily produced in South America, Africa and the broader Asia-Pacific region. These dynamics suggest that future value creation may increasingly shift toward non-U.S. markets that control supply chains for strategic commodities, with earnings upside potentially accruing to companies and economies outside the United States.

Semiconductor and Mining Production by Location

(Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management, as of April 25, 2025)

A Temporary Pause or Structural Shift?

Despite these headwinds for U.S., it is probably premature to declare an outright end to U.S. exceptionalism. The policy mix under Trump may have introduced volatility, but its macroeconomic impact remains limited compared to historical crises. And we still have not seen what this administration might offer in terms of corporate tax cuts or regulatory reform. Moreover, global markets outside the U.S. still face significant hurdles in achieving sustained earnings growth, while the war between Russia and Ukraine and tensions between China and Taiwan underscore the geopolitical risks present in international equities.

What seems more likely is a temporary pause in U.S. dominance rather than a complete reversal. This pause could allow other regions to catch up slightly but does not yet signal a fundamental shift in global leadership. Of course, that may beg the question: What would signal more fundamental, multi-year change in this trend? Here are a few potential themes our Investment Committee is watching:

- Continued expansion of international deficit spending, especially Europe, along with some indications of U.S. fiscal tightening

- Additional AI and tech-related competition like the DeepSeek news in January

- The implementation of long-term, structural tariffs that lead to a spike in U.S. inflation readings

- A prolonged decline in the U.S. dollar; the last period of international outperformance over the U.S. was 2001 to 2008, which coincided with a sharp dollar fall

- A slowdown in U.S. consumer spending and/or a spike in unemployment

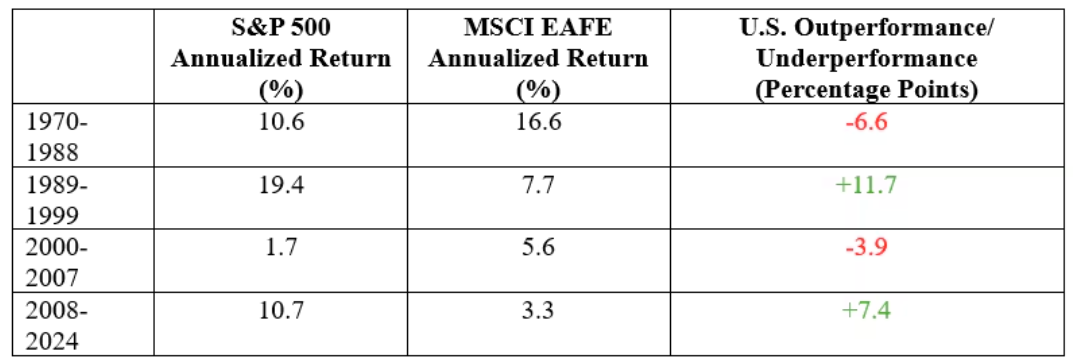

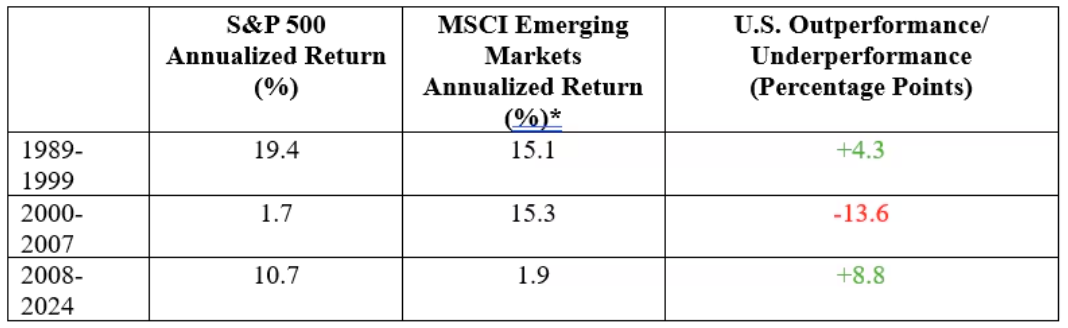

Historical Periods of U.S./International Equity Relative Performance

U.S. vs. International Developed:

U.S. vs. Emerging Markets:

(Source: Morningstar)

Lessons from the Past

We’ve seen similar dominance before. In the late 1980s, Japan enjoyed a similar dominance in the global markets. At its peak in 1989, Japan made up over 40% of the MSCI World Index—more than the U.S. at the time. Investors believed Japan had cracked the code: industrial dominance, rising asset values, and global admiration for its corporate and economic model. Back then, seven of the world’s 10 largest companies by market capitalization were Japanese. Today, not a single Japanese company is in the top 10, and Japan now represents around 5% of global equity market capitalization.

The story of Japan is a reminder that market leadership is not a given. Structural advantages can erode and investor sentiments can shift, especially when demographics, policy missteps or overconfidence get in the way. For those who believe U.S. dominance is permanent, it’s worth remembering that the future rarely follows a straight line.

Final Thoughts

There’s little doubt that the extended period of U.S outperformance and the extreme concentration in U.S. large-cap technology—particularly the Magnificent 7—has created significant imbalances in many portfolios, leaving them exposed to heightened idiosyncratic risks. This underscores the value of a more deliberate approach to U.S. exposure, focusing on broader market participation and diversification beyond the dominant tech giants whose valuations have been stretched by the past several years of AI enthusiasm.

More importantly, this pause in U.S. exceptionalism presents an opportune moment for investors to reassess their international allocations. Many U.S.-based investors remain significantly underweight in international equities relative to global benchmarks like the MSCI ACWI. While we stop short of predicting a full and extended reversal of U.S. dominance, the improving fundamentals across international markets create a compelling near-term case for international equities.

Of course, when considering how much to allocate to international equities, there is no universal answer. The right allocation depends on various factors unique to each investor, including investment objectives, risk tolerance, time horizon, spending rate and overall portfolio goals. Our team is pleased to discuss these considerations with any nonprofit organizations considering the right U.S.-to-international equity blend in their portfolio today.